How Corrupt is Nigeria? By Kolawole Olaniyan

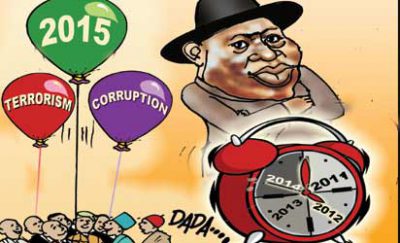

How corrupt is the government of President Goodluck Jonathan? The answer may vary depending on who is interpreting the latest global corruption index from Transparency International.

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2014, Nigeria is up eight places to 136 out of 175 countries ranked by the index.

The government has unsurprisingly interpreted this to mean that Nigeria is “winning the war on corruption under President Goodluck Jonathan’s watch.”

The government has also said in a rather celebratory tone that, “It may not be immediately apparent to those who do not understand the dynamics of applying creative techniques in upturning an age-old habit that has cost this country a lot in terms of financial resources; but to those like the officials in Transparency International knowledgeable in the nuances of fighting corruption, a lot of grounds have been covered.”

Two central observations become clear; firstly, the statement seems to take a dig at government’s critics for lacking “creative techniques” in the fight against corruption. But creative techniques? I’m sorry; no serious observers of the government’s record will succumb to this cheap shot. Secondly, the government also may be accused of inconsistency and political opportunism because having previously questioned the validity and credibility of the index, now seems to be its strongest ‘apostle’ by suddenly acknowledging the ‘knowledge’ of Transparency International “in the nuances of fighting corruption.”

The government’s response is nothing more than a standard public relations tactic. But this triumphal tone needs to be moderated; and the government’s real record in the fight against corruption has to be placed in proper perspective.

The country’s current ranking is clearly better than its scores for 2013 but it doesn’t really tell us something we don’t already know: that this government is still considered highly corrupt, as the country still ranks in the bottom half of the index. As a matter of fact, Nigeria shares 136th position with well-known corrupt countries like Cameroon, Kyrgyzstan, Iran, and Lebanon.

The CPI ranks countries on a scale from 0 (perceived to be highly corrupt) to 100 (perceived to be very clean). More than two-thirds of the 175 countries surveyed, including Nigeria, scored below 50. Nigeria is clearly not the country with the lowest score on the index (its score was 27%), but according to Transparency International, any country that scores below 50% on the index is still considered “highly corrupt.”

This shows that corruption is rife as it ever has been in the country, making this government one of the most corrupt on earth

This is therefore no time to feel comfortable with Nigeria’s sheer mediocrity on the index. But the government’s response says something about diminished expectations for a country that is endowed with enormous human and natural resources and should be doing much better in terms of socio-economic and infrastructural development to see the 27% on the index as good news.

Millions of Nigerians who continue to live from hand to mouth, unsure of the next meal, while their ‘leaders’ enjoy the commonwealth with their families and friends certainly won’t celebrate this score. And they won’t celebrate a score that still shows a serious breach of the country’s international anti-corruption obligations and commitments.

It would seem that the government doesn’t even understand the depth of disgust Nigerians feel for the increasing level of corruption among high-ranking government officials and the impunity of perpetrators.

For many years President Jonathan has devoted dozens of speeches to rooting out corruption. For example, the President once promised to “fight for justice, for all Nigerians to have access to power, for qualitative and competitive education, for healthcare reforms, to fight corruption, and to fight for your rights.” But it is now another election time and he has not even published his asset declaration (to show the way in the fight against corruption) let alone “fight for your rights”!

Under the President’s watch, no high-ranking public officials has ever been brought to account for corruption, despite widespread and increasing allegations of corruption at the highest level of government.

By celebrating a marginal movement on the index, the government isn’t focusing on the job of fully and effectively combating corruption by high-ranking public officials. Instead, it is downplaying the magnitude of the problems, and seems to be kidding itself and kidding millions of Nigerians. This is unwarranted, counterproductive, and on balance, does more harm than good.

This government has to come clean and be straight with the Nigerian people on its record in fighting corruption.

But Nigerians are not fooled, as they are very aware of the lack of integrity, trust and credibility of their political institutions and the lack of quality behaviour from their politicians generally. They know pretty well that corruption is still a major problem in Nigerian politics, with various government agencies becoming deeper and deeper involved with the widespread use of political appointments even at the highest level of government.

The simple fact of the matter is that Nigeria’s corruption is now institutionalised into the political system and where democracy has been replaced by “Nairaraincracy” (or more accurately “Dollaraincracy”, as most of the country’s politicians consider US dollar as the legal tender) and where politicians are elected to provide self-serving favours to donors and “godfathers”.

It is clear that the government is still largely run for the benefit of the very rich and socially and politically connected. When people say, ‘it is not what you know but whom you know’, there is a problem.

Corrupt judiciary and weak anti-corruption mechanisms well illustrate the damaging lack of political will by this government to confront corruption and impunity of the corrupt. Serious human rights violations, including poverty, crimes against humanity and the environment are now considered normal.

Yet, lack of prosecution of high-ranking government officials for corruption has created an impression that they are above the law. No wonder, then, that corrupt officials are so unfazed in their wrong doings, they are all doing it openly and lavishly and don’t even bother to hide their misdeeds.

Unfortunately, the more corrupt the country becomes, the less motivated its leaders and politicians are to end it. This doesn’t present much hope for the future.

But we can’t simply throw our hands up in the air in frustration. Progress is not only possible but necessary as it is simply unacceptable to continue with ‘business as usual’. The government will need to get to work and move swiftly to improve the independence and freedom of action of the anti-corruption agencies to genuinely fight corruption. These agencies should be free to investigate and prosecute any allegations of corruption, not just those the government has a partisan interest in seeing pursued.

It is time for the government to let the country’s anti-corruption agencies off the chain and allow them to prosecute those indicted by: the KPMG report, involving large-scale corruption in the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC); the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) audit report, which exposes 10 years of corruption in the upstream and downstream sectors of the oil and gas industry; ‘pension funds corruption report’; ‘corruption report’ in the capital market, and of course the case of the missing $20 billion from the account of the NNPC.

Some level of transparency and accountability won’t hurt the country. In fact, it will ensure better governance and the returns for effective enjoyment of human rights by the citizens will be huge.

One can only hope that the government will wake up and genuinely begin to address corruption and associated human rights violations. Nigerians deserve this. The success (and sustainability) of the country’s democracy depends on this.

And this is the most important promise for the politicians to take to the February 2015 elections and subsequently keep if elected.

Olaniyan, author of ‘Corruption and Human Rights Law in Africa’, is Legal Adviser, International Secretariat of Amnesty International, London.